Your Phone, Your Call - Part II - Whatever Happened to Caller ID

Time to read:

A version of this originally appeared on Marketing Land

Way back when the Internet was young, and early internet surfers were using 3600 baud modems to launch themselves via copper into the Netscape driven cyberverse, trust and identity were not really as important as they are today. Flash forward to today: Identity and reputation both play a critical role for re-establishing trust across digital communications. Who calls or emails us and their credibility (whether the caller or sender is someone who’s credible enough and worth the time of the recipient to respond) are key elements that help us decide whether to take a call, open an email or respond to an SMS. Precautions, such as two factor authentication, is based on the fact that we can’t trust just one form of identity. I hate to sound like an alarmist, but the Internet can be a scary place. This is why we introduced Verified By Twilio at our SIGNAL 2019 conference. Verified By Twilio is our initiative to provide consumers with the context to know exactly who is calling them and why in order to limit unwanted calls and improve answer rates for legitimate businesses and organizations.

There are a number of other technologies and initiatives aimed at ensuring trust. For me, as someone who appreciates the history of digital communications, it’s interesting to see all of these efforts trying to accomplish something that was invented more than 50 years ago: caller ID. Remember caller ID from the good ol’ landline days...where you could view the number that was calling you on your phone and see or hear the caller’s name and location?

Caller ID: Where has it gone?

The short answer is: caller ID still exists, but it’s a lot more complicated than you think.

When I said that it’s more than 50 years old, I wasn’t kidding. Caller ID was invented in 1968 by Ted Paraskevakos – long before cell phones were even an idea. The system that Mr. Paraskevakos invented (and Kazuo Hashimoto perfected in 1976) boiled down to this: when a person dialed another person, their phone sent a signal through the wires to the recipient. Landline numbers were (and today often still are) tied by physical wires connected to the local phone company’s central switch. In those days, a number was always identified with a specific address and location. Caller ID simply matched the number and location with the subscriber’s name and location.

How cell phones complicate caller ID

The advent of cell phones made the caller ID process more complicated. Cell phones now dominate phone calls. Nearly 55% of US homes in 2018 did not have a landline – only a cell phone. That number jumps to 77% when you only count millennials (aged 25-34)! The basic technology of cell phone calls involve the use of any number of various stops between multiple carriers. In the U.S. alone, there are more than 1600 phone carriers, all with their own networks and sources for caller information. A cellular call is not tethered nor dependent upon physical landlines. In the old days of landlines, your neighbor down the street was on the same network that you were on. Nowadays, your neighbor might be on AT&T’s network and you might be using Verizon’s, regardless of the fact that you live around the corner from each other. Just imagine how many places a signal has to travel to connect you to family and friends that may live in the next suburb let alone halfway around the globe. The complexity is mind boggling.

In the early days of cell phones, caller ID was largely dependent on the contact list stored in someone’s cell phone. For the most part, during those days, the only people calling each other were people who knew each other. From a product perspective, wireless carriers in that era didn’t see caller ID as critical as other services – like text and voice mail – because of the prevalence of the contact list. A lot of consumers felt they already had caller ID, and still do today. But, in reality, as has become apparent in an age of robocalls and rampant phone scams, the majority of consumers do not have caller ID, and trust in the overall communications process has plummeted.

There’s a link here with how companies viewed address books for email marketing. A brand who managed to get their recipient to add their from address to their email client’s address book benefited from improved inbox placement. Similarly, caller ID helped establish credibility when a company calls to schedule delivery or returning a customer service call. Again, we live in an era of trust but verify because our communication channels and platforms have been exploited.

Caller ID comes to cell phones

The wireless carriers did eventually get around to offering true caller ID in 2011 for around $3-5/month. The delay was partly because smartphones – which could accommodate the complex caller ID process – didn’t hit the market until 2007.

But the main reason caller ID wasn’t a priority? Because it really wasn’t needed—until the plague of robocalls, spoofing and phone scams started to become ubiquitous. That led to a demand for caller ID with a name attached to a number that showed up on the phone.

And now:

- T-Mobile offers services like Scam Likely and Scam ID

- AT&T customers can opt-in to services such as Call Protect and Call Protect Plus

- Verizon has Call Filter while Sprint offers Premium Caller ID.

- iOS 13 will give iPhone users the ability to route all unknown calls to voice mail thus preventing the delivery of robocalls, but legitimate calls in the process, how many of you store the number of your Doctor’s Office, and is it consistent for inbound and outbound?

The problem is, fewer than 5% of consumers have opted in to caller ID and name services on their cell phones. Again, caller ID has been available -- it just hasn’t been widely utilized by consumers.

And now, even with traditional caller ID enabled on their cell phones -- like we used to have on landlines -- consumers may still not know who is calling them.

The reason? Spoofing. In its simplest form, spoofing a number or email address means the sender is pretending to be someone they are not when placing a call or sending an email. There are legitimate use cases for spoofing, such as a doctor’s office calling you, or the placing of a call by a ride sharing app to protect the driver’s and the callee’s personal information. In an age when the phone system is no longer tethered by copper, but has gone virtual thanks to SIP calling, bad actors (and some good) can decide who they want to be when calling you. They can even call you from your number! Today’s caller ID system only uses the phone number associated with the incoming call to lookup the name and location of the owner of that phone number in the database. That doesn’t work with spoofing when a call might appear to be from someone you know, but in reality it may be someone with malicious intent spoofing their number to trick you into answering it.

So while caller ID still exists today and is readily available, it doesn’t instill enough trust for you to answer the call. There really hasn’t been a way to prove that the person making the call is indeed who they say they are.

The New (Old) Era Of Communications

Spoofing is why the communications industry is now starting to roll out a new technology known as STIR/SHAKEN. STIR/SHAKENtands for “Secure Handling of Asserted information using toKENs” and “Secure Telephony Identity Revisited.” Simply put, with STIR/SHAKEN, the service provider that originates a call onto the public telephone network will cryptographically sign the caller ID and called number with a private key so the call can transit the networks securely. Upon reaching the terminating carrier, a public certificate is used to decrypt and verify the call.

Under this scheme, when a call finally reaches its destination it might be accompanied by a check mark or some other indicator to signify it’s been certified as a legitimate call. Even for certified calls, the end user must still decide whether to take or reject a call based on the information they have.

The process is very similar to how websites currently handle trusted communications. Certification authorities (CAs) issue digital certificates verifying the authenticity of websites and their content. As a result, a user knows they are visiting a legitimate website, as opposed to one that has been setup to capture or steal information. This process is somewhat mirrored in the inbox by those little green and red lock icons you see in certain email clients that denote if the message was transmitted using TLS or if it failed certain authentication checks. This concept is finally coming to your mobile handset—and just in the nick of time! By some estimates, there are 9,500 fraudulent robocalls per second!

Times they are-a-changing!

In November 2018, Ajit Pai, the chairman of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), required carriers to implement the STIR/SHAKEN framework to help establish the validity of placed calls by connecting callers and numbers through cryptographic signing. Remember caller ID? Knowing who called and being able to, with confidence, attest to the validity of that caller is critical to combatting spoofed calls and robocalls. Although STIR/SHAKEN won’t tell you exactly who called, it will provide a visual indicator that the caller owns the number initiating a call and help in tracing fraudulent calls. If a carrier can “automagically” tell that a call isn’t who it claims to be, or from whom it purports to have originated, then they can simply not deliver that call. This is pretty much how email authentication protects us from the rash of phishing attacks.

Earlier in the year I wrote about the history of email in a 3 part series. Email had/has a similar authenticity problem: how do I know that the email I received actually came from the brand or person that claims to have sent it? As I said then, email was built at a time when trust and identity wasn’t as important. As the Internet matured and more of us came online, bad actors saw email as a highly exploitable channel. Standards bodies, such as the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), and their members took it upon themselves to create mechanisms to identify legitimate senders and drop the mail of bad actors pretending to be a legitimate brand. This potent mix of standards is now known as SPF, DKIM and DMARC.

The problem of phishing and spoofing in email is by no means solved. Bad actors continue to evolve their attacks. Simultaneously, the channel is thriving through evolutions such as Google’s AMP for Email and the renaissance that newsletters are having. As the title suggests: everything old is new again!

What’s next?

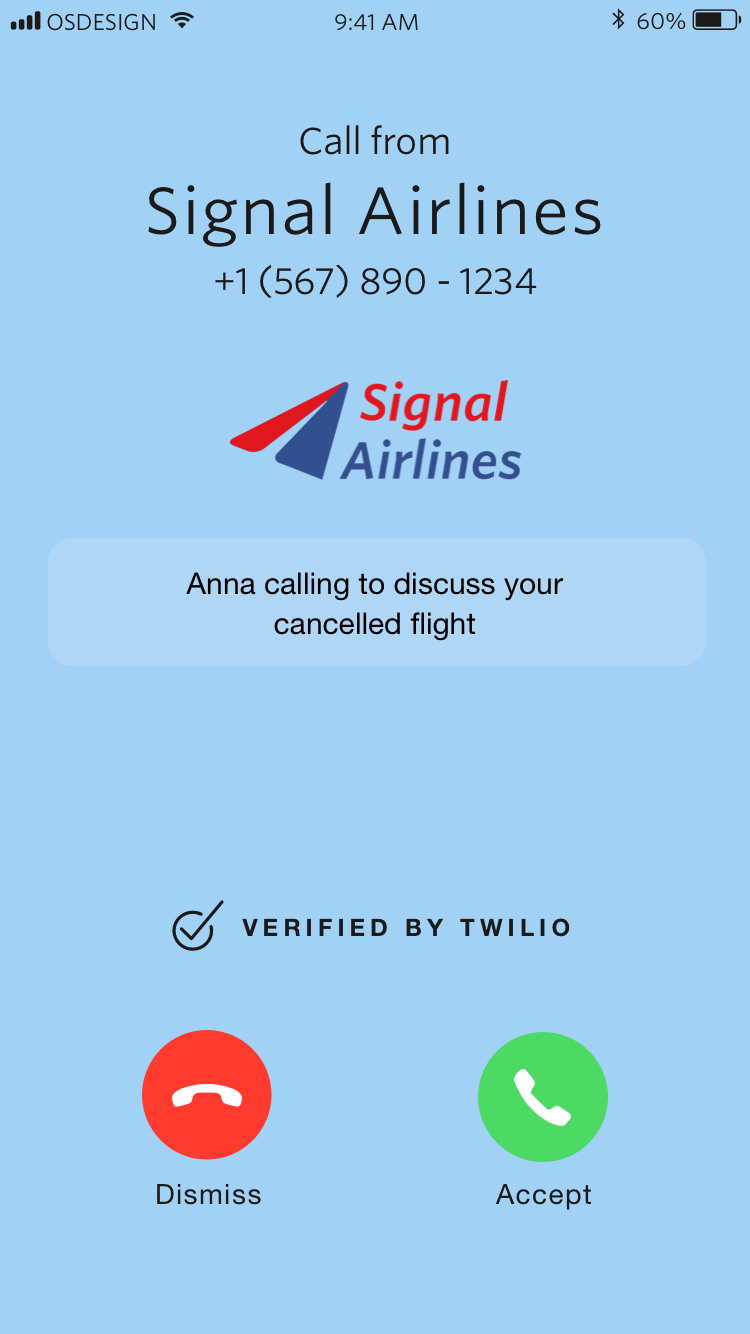

But wouldn’t it be great if the consumer had more information than just a green check mark? For me personally, I’m not sure that would be enough to instill enough confidence to answer a call from a number I had not seen or heard of before. Verified By Twilio addresses this by not only verifying the call by the time it gets to someone’s phone, but also making sure that the actual brand of the business or organization that is calling appears on the screen, along with why they are calling. For example, if an airline company is trying to contact a customer about a cancelled flight, as the call comes in, the consumer will see the name of the airline with a short note indicating why they are calling. With that information, that person can make the decision about stepping out of a meeting or putting another call on hold to answer this critically important call.

The image on the phone would look something like this:

Verified By Twilio is currently available to consumers who have downloaded one of the following caller identification apps: CallApp, Hiya, Robokiller, and YouMail. It is an initiative we hope will be embraced across the industry. We have opened it up to private beta and welcome applications from businesses and organizations—such as carriers and operating systems, in addition to apps—to participate start by visiting twilio.com/verified-by-twilio.

The Mission to Regain Trust

The way we interact with our phones is changing. Similarly, our inboxes are changing thanks to the likes of Google and the much anticipated BIMI (Brand Indicators for Message Identification). which rewards companies who sign email authentication for their emails, at enforcement, with brand logos next to their messages in the inbox. Trust and identity are at the center of much debate and controversy around Internet technologies. Recently, I had the pleasure of leading an on stage conversation with some of the authors of DKIM/DMARC and STIR/SHAKEN. If you’re interested in learning more about how these technologies are shaping the way we communicate, check out this video.

One wonders what the inventors of the original version of caller ID on landlines would think about today’s various technologies and efforts to pursue trusted communications—caller ID services from carriers, apps, STIR/SHAKEN and a number of other initiatives. All of it is needed to regain that sense of trust and faith in the phone call and inbox that we all took for granted during the golden age of landlines and the earliest days of email. The complexity of today’s communications process by default demands complex solutions and industry-wide cooperation. But industry-wide cooperation is not anything new. After all, carriers and system providers cooperated in the old days of landlines, too. There may have been less of them, but still, the cooperation was there. I believe that same sense of cooperation exists today, too, just on a bigger scale. Caller ID, innovation, trusted communications, industry cooperation—the more things change, the more they are the same.

Len Shneyder is a 15+ year email and digital messaging veteran and the VP of Industry Relations at Twilio SendGrid. He can be reached at lshneyder [at] twilio.com.

Related Posts

Related Resources

Twilio Docs

From APIs to SDKs to sample apps

API reference documentation, SDKs, helper libraries, quickstarts, and tutorials for your language and platform.

Resource Center

The latest ebooks, industry reports, and webinars

Learn from customer engagement experts to improve your own communication.

Ahoy

Twilio's developer community hub

Best practices, code samples, and inspiration to build communications and digital engagement experiences.